14. The Enlightenment

Overview

"...in the middle of the eighteenth century, Voltaire ruled unchallenged over

France and over civilised Europe. They had finally discovered and proclaimed

liberty over the ruins of fanaticism. They sang, especially after drinking, about

tolerance and brotherhood; they kissed passionately and even the most

restrained wept tears of joy for humanity; it was truly wonderful to see... Men

had finally become so perfectly happy that they could move beyond God and

replace him, to their advantage, with philosophy and reason" (Les prisons du

marquis de Pombal, August Carayon, 1865)

The term "Enlightenment" generally refers to an intellectual movement in the 17th and 18th

centuries in Europe (commencing around the end of the English Civil War and concluding at the

beginning of the French Revolution) and overseas colonies, in which ideas about God, reason

(induction), nature (the universe being ruled by natural law) and mankind were blended into a

new non-Christian worldview that gained wide assent and instigated revolutionary developments

in art, philosophy, and politics. From a theological standpoint, it signalled increasing

secularisation of society and emphasis on humanism that flowed from the Renaissance and

continues to this day.

These changes occurred at the same time as social reforms driven by concerned Christians,

revivals in Europe and North America, including the Great Awakenings, and worldwide missions

initiatives. A lot of uncritical commentary about the Enlightenment fails to acknowledge the

work occurring at the same time by the world-wide Christian community. It also misses the

point that, while the leaders of the Enlightenment were at the height of their popularity, they

were in the minority; the majority of people continued to believe in God and go to church.

What Led to the Enlightenment?

Religious Factors

- Collapse of power of (and trust in) the institutional church, owing to corruption, internal

politics, lack of responsiveness to broad social developments and learning, superstitions

and charlatans (eg the ongoing trade in relics) and dissatisfaction with deep divisions in

Christianity (Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox, others).

- Questioning of creeds and established beliefs, including theological positions that

resisted/rejected scientific discoveries and human development. By rejecting scientific

developments the church was labelled out of date and ignorant.

- Some of the leaders of the Enlightenment were, in fact, trained Catholic clergy,

whose beliefs were out of sync with mainstream teaching.

- Rejection of teaching such as Christ's resurrection suited a re-focus on humanism

- Emergence of strong (fundamentalist) Protestant movements that encouraged nonconformity

with many traditional (extra-Biblical) religious forms, on the one hand but

arguably ended up creating liberalism and vacuums of belief, on the other.

Political Factors

- Political upheavals across Europe and colonies (eg the American colonies, contributing to

a war for independence), including religious conflicts; led to coalitions, breaches with

alignments; searches for compromises (a desire to find beliefs everyone could agree one)

that pursued peace at the cost of tradition.

- Enlightenment "superiority"/paternalistic thought encouraged empire building.

- Emergence of consolidated nation states, whose leaders only paid lip service to

dominance by the church and were happy to demonstrate their independence by

humbling Rome, suppressing the Jesuits, backing rival sides in the church and

expropriating church property (or exploiting religious divisions for political ends). There

was, in effect, a power/influence struggle between the state and the church.

- Eastern Europe continued to be pressed by Muslim invaders; after a 2-month siege of

Vienna, which ended on 12 September 1683, the Ottoman retreat began; this conflict was

seen as a geopolitical event, not a religious one. Church leaders were expected to limit

their role to spiritual matters, meaning the role of the church in society was re-defined.

Social/Economic Factors

- Transition from agrarian to urban, industrial societies, fundamentally transforming the

way people lived, interacted and thought: "modernity" mocked "superstitions" of the

Middle Ages

- Dislocation, travel -more than ever before - leading to openness to new ideas.

- Emergence of a wealthy, educated middle class.

- Emergence of new forms of learning - disillusionment with traditions, forms and

structures that allowed little questioning/enquiry.

- Emergence of concepts such as liberalism, capitalism, freedom (including a free press),

individualism, equality, democracy, pluralism, self-determination, independence and

religious toleration.

Deism

Deism is not a religion but a perspective on the nature of God.

- Deists believe that a creator God does exist, but that after the motions of the universe

were set in place He retreated, having no further interaction with the created universe

or the beings within it.

- Because the deist God is no longer involved, he has neither need nor want of worship.

- Deists commonly hold that God does not care whether humanity believes in Him.

- Because God has no desire for worship or other specific behaviour, there is no reason for

him to speak through prophets, nor send representatives of Himself among humanity.

- God, in his wisdom, created all of the desired motions of the universe during creation.

There is therefore no need for Him to make mid-course corrections through the granting

of visions, miracles and so forth.

- Because God does not manifest Himself directly, He can only be understood through the

application of reason and through the study of the universe He created.

- Deists stress the greatness of creation and the faculties granted to humanity, such as the

ability to reason. As such, they reject all forms of revealed religion. Any knowledge one

has of God should come through one's own understanding, experiences and reason, not

the prophecies or traditions of others.

- Because deists accept that God in not interested in praise and that He is unapproachable

via prayer, there is little organized religion surrounding deist beliefs.

- Deists believe that organized religions add layers of untruth to the reality of God. Some

deists, particularly historical/cynical ones, however, see a value in organized religion for

the common folk, because religion could instill positive concepts of morality, sense of

community, compliance with traditions and obedience of authority for eternal reward.

Some Influential Public Figures During the Enlightenment

French

The more notable figures in the Enlightenment were French thinkers known as philosophes:

Voltaire (1694-1778), aka François-Marie Aroused, Deist, writer, historian, poet and critic

of the church and Christian doctrine. He emerged as the Enlightenment's chief critic of

contemporary culture and religion. Voltaire wrote at a time when a corrupt state Church

and totalitarian government exercised control over nearly every aspect of French life.

He reasoned that the best way to break the Church's hold on people's hearts and minds

was to make his fellow citizens doubt its core doctrines. He also influenced Thomas

Paine and other American revolutionaries and helped lead thinking up to the brutal

French revolution.

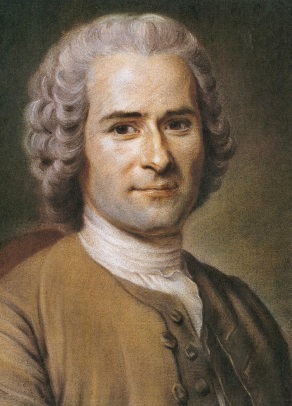

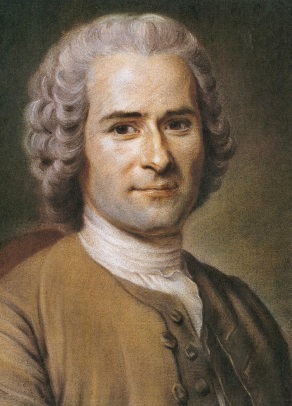

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), whose writings (eg, man, if left to himself, is noble

and good) greatly influenced the political thinking of his time.

- Voltaire and Rousseau died the year before the beginning of the French

Revolution.

Charles, Baron de Montesquieu(1689-1755) challenged the idea of rule by a monarch and

championed individual freedom. Strong proponent of separation of church and state.

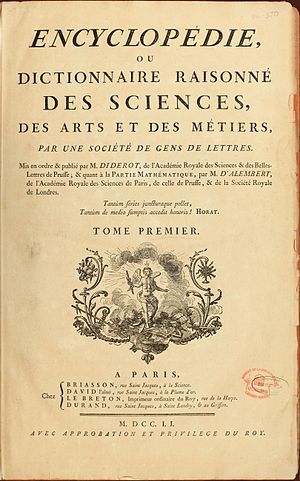

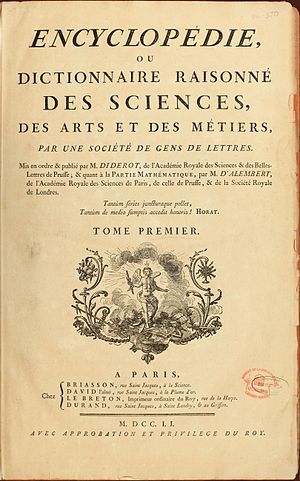

Denis Diderot (1713-1784) - in collaboration with Jean D'Alembert, founded the multivolume

Encyclopédie designed to include all realms of knowledge. The work contained

many articles attacking or critical of organised religion and Christian belief.

Voltaire

Rosseau

Diberot's Encyclopédie

German

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), philosopher and physicist, wrote on ethics and morals and

prescribed a politics of Enlightenment.

Johann Gottfried von Herder, theologian and linguist, proposed that language determines

thought.

Several European monarchs during this period, including Frederick the Great of Prussia,

Catherine the Great of Russia, and Joseph II of Austria, were known as enlightened despots (!?)

because they supported the ideas of the Enlightenment.

British

Adam Smith (1723-1790) - philosopher and economist - Smith was a Scottish philosopher

and economist who is best known as the author of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes

of the Wealth Of Nations (1776), one of the most influential books ever written.

David Hume (1711-1776) - philosopher and historian

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) - philosopher

North American

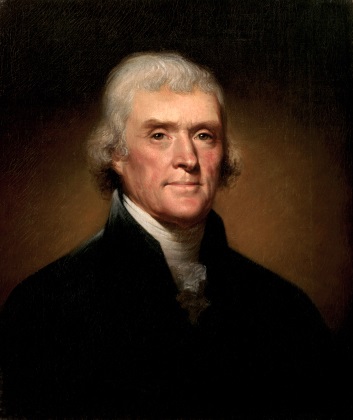

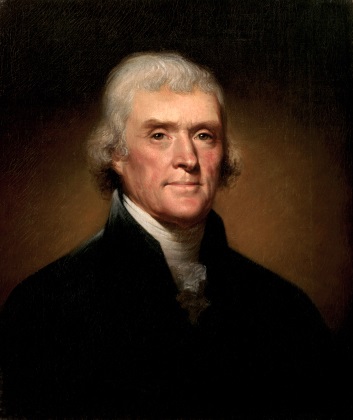

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) - a Founding Father of the USA, the main author of the

Declaration of Independence and the third American President. A spokesman for

democracy and the rights of man with wide influence; critical of the church, advocate for

individual religious belief.

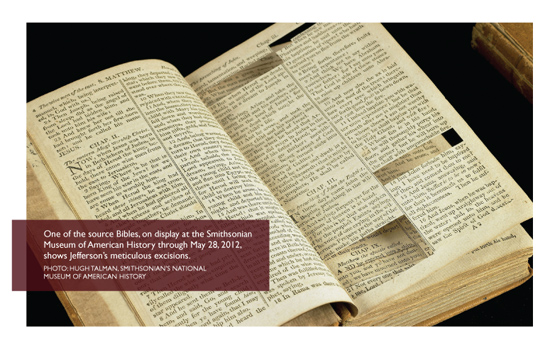

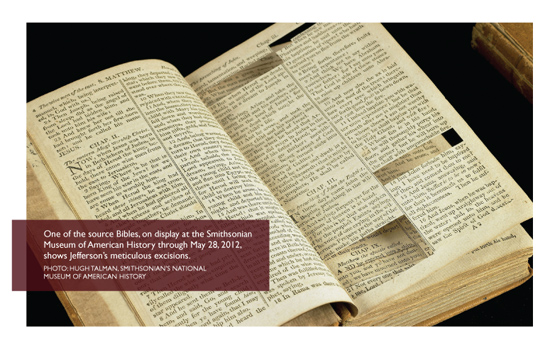

- To some leaders during the Enlightenment, the Bible was seen as a useful source of

moral content and teaching, as long as readers did not take it too literally or believe

parts of the Bible that they could not reduce to "reason", eg miracles, faith, New

Birth, or the Second Coming of Christ.

- Jefferson (in 1804) redacted the Bible and produced The Jefferson Bible, or what he

called The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, by cutting out and pasting parts that

he liked and omitting parts he did not agree with, including the miracles of Jesus and

any suggestion that Jesus is God. The virgin birth is gone. So is Jesus walking on

water, multiplying the loaves and fishes, and raising Lazarus from the dead.

Jefferson's version ends with Jesus' burial on Good Friday. There is no resurrection;

no Easter Sunday. Jefferson called the writers of the New Testament "ignorant,

unlettered men" who produced "superstitions, fanaticisms, and fabrications". He

called the Apostle Paul the "first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus". He dismissed

the concept of the Trinity. He believed that the clergy used religion as a "mere

contrivance to filch wealth and power to themselves" and that "in every country and

in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty".

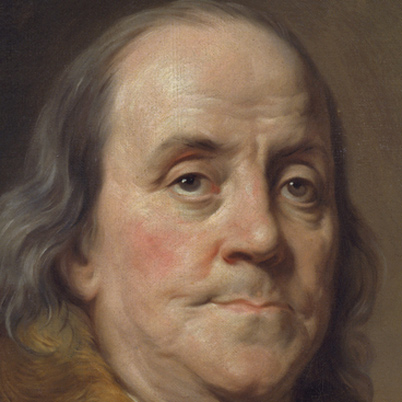

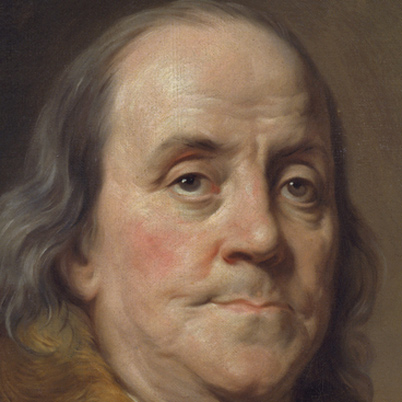

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) - a Founding Father of the USA, helped draft the

Declaration of Independence, sixth American President. Scientist, diplomat, author,

philosopher. Claimed to be a Christian but was liberal in terms of theology, and a deist.

Thomas Paine (1737-1809) - English-American political activist, author (writer of The

Rights of Man), political theorist and revolutionary. His Common Sense (1776) was a

central (Deist) text behind the call for American independence from Britain. Paine

promoted reason and freethinking and argued against institutionalized religion in general

and Christian doctrine in particular.

Jefferson's Bible

Jefferson

Benjamin Franklin

It is important to understand that many of these figures claimed they believed in God (atheists

came later in the Enlightenment history and founded the basis of their atheism on the mistaken

theism of the early Enlightenment).

Enlightenment versus Christian Belief - A Critique

1. The Enlightenment is sometimes viewed (by its supporters) as a movement in which the

"human race awoke from its mental bondage and lethargy and entered into intellectual

maturity". According to philosopher Immanuel Kant, the Enlightenment was "the emergence of

man from his self-imposed infancy".

- Those who write such things are being both intellectually dishonest and reductive,

because they infer there were no genuine enquiry, learning or real knowledge prior to

them; and because expressing things this way appears to be taking cheap (populist)

shots.

2. Central to the Enlightenment were the use and the celebration of Reason. Rationalism starts

with the mind or thought, the power by which man thinks and understands the universe, and

ends up with the explanation for everything in logical format. The goals of "rational man" were

considered to be knowledge, freedom and happiness - without God or religion.

Early rationalists showed a distaste for late Mediaeval attachment to the likes of Aristotle, and

scholasticism, and made the starting point knowledge of self rather than knowledge (and

understanding) of God.

- The most famous case of this is the philosophy of Rene Descartes, who, in a search for

first principles, declared "Cogito ergo sum" (French: Je pense, donc je suis; English: I

think, therefore I am). Starting with this premise, he made it his point to prove nearly

everything, including God, by thinking and his own logic.

- Relying on the rational faculties of every individual, the results can be random, diverse

and inevitably contradictory. Approaching the great questions of life from this direction

also puts doubt first.

The Enlightenment movement advocated "reason" as the sole basis of ethics, knowledge and

behaviour. Its leaders regarded themselves as courageous and elite, and viewed their purpose as

leading the world towards progress and out of a long period of doubtful tradition, perceived as

irrationality, superstition and tyranny (the so-called "Dark Ages").

As we have seen in this course, there was spiritual darkness during the Mediaeval period

(as there is in every age), vested interests did not allow open enquiry, but there were

also, always, Christians who pursued a Biblical world view and message.

Christ has taken us out of darkness into His light (1 Peter 2:9). That is "enlightenment".

During the Enlightenment, people were taught that unending progress in knowledge, technical

achievement and moral values would be possible. Following the philosophy of John Locke, 18thcentury

writers believed that the human mind begins as a blank sheet and that ideas and

knowledge come only from experience and observation guided by reason.

Read Romans 3 for a description of human nature (and its capabilities) without God.

Consider also 1 Corinthians 3:19 and James 3:15

Although they claimed that they saw the church as the principal force that had "enslaved" the

human mind in the past, most Enlightenment leaders did not renounce religion altogether. They

opted rather for a form of Deism, accepting the existence of God and a hereafter, but rejecting

most Christian theology.

- "... having a form of godliness but denying its power." (2 Timothy 3:5)

- "You believe that there is one God. Good! Even the demons believe that—and shudder."

(James 2:19)

3. In contrast to earlier eras in which (in Christendom) popes, priests, tradition, and the Bible

were the authorities, the Enlightenment emphasised the authority of reason, of the individual

("I am the master of my destiny!") without God, over revelation. It stressed the overall

goodness of people; while acknowledging that people could act wickedly; views concerning

original sin and the depravity of man were replaced with an optimistic perspective concerning

human nature: man could overcome evil on his own effort through reason and education ....if he

is so inclined, cf Jeremiah 17:9; Romans 3:10-19

We only know Christ through divine revelation (Luke 10:22; John 6:44, cf Matthew 16:17);

not persuasion of reason. In fact, our minds need to be "renewed" (Romans 12:2).

Enlightenment writers were mistaken in their assertions that belief in God and the use of

reason (God-given, after all) were in conflict. The Christian faith is a reasoning faith.

Reason is not used to create belief, but is a tool with which faith and understanding of

Christianity can be explored and expanded.

Where there is conflict between God and human reason, "Let God be true, and every

human being a liar." (Romans 3:4)

4. Human aspirations, rationalists believed, should not be centred on the next life, but rather on

the means of improving this life. Happiness now was placed before salvation in the future.

Nothing was attacked with more intensity and ferocity than the traditional Church.

- Consider the Bible's eternal view: "If only for this life we have hope in Christ, we are of

all people most to be pitied". (1 Corinthians 15:19)

- This life is not enduring (Matthew 24:35; James 4:13-15)

- Christians are called on to proclaim Christ, a new life and good works throughout this life

(salt, and light, bringing glory to God), but with a clear focus on eternity. Christians are

not meant to be hermits, but to live in the world, in the power of a new life (a common

theme in the Pauline Epistles).

5. Also characteristic of this new 'Age of Reason' was optimism about the betterment of society.

Reason, education, science, and technology were believed to be ushering in a "technological

Messianic" age in which many of the world's problems would be solved. The Enlightenment

stressed the equality of all persons, believing that all were endowed with natural rights. It

rejected the traditional view of the "divine right of kings" in which rulers were viewed as

deriving their authority directly from God and (by extension) resisting injustice was a sin. There

were exceptions to Enlightenment optimism, eg Rev John Malthus (1776-1834), who had views

about famine, disease and natural disasters and their roles in keeping world population in check.

Christians believe the only way to renew society is through a new creation (2 Corinthians 5:17).

6. The Enlightenment spawned the discipline of biblical criticism which became popular in the

major universities of Europe. There was no place left for the supernatural. Miracles and

supernatural accounts in Christianity were rejected; they were viewed as being incompatible

with reason. As a result, the Bible was subjected to unrelenting criticism. Traditional

authorship of the Bible was rejected and anything supernatural was dismissed or reinterpreted.

While some Enlightenment thinkers still embraced traditional Christianity, the Enlightenment

gave birth to growing numbers of atheists, agnostics and Deists. For instance:

- David Hume's scepticism and atheism left no room for God or the miraculous, arguing, for

example, that miracles violate the laws of nature and are therefore improbable.

- Immanuel Kant, while himself a believer in God, laid the philosophical basis for

agnosticism by arguing that the non-material realm was totally unknowable by reason.

Thus, nothing about God, the soul, or the afterlife could be known through reason.

- Deists like Thomas Jefferson believed that the existence of a creator was compatible

with reason but this creator was not the Christian God and certainly not a being who

cared about or dealt with humans. It was this rejection of traditional Christianity that

led to the birth of liberal Christianity.

- Deists believed that God was "deus absonditus", like a watchmaker who sets the

universe in motion but thereafter walks away and does not intervene in human

affairs after that.

- The founder of liberal Christianity - Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) - attempted to

adjust Christianity in such a way that his version of religion could be palatable to modern

man. In so doing, though, he rejected traditional Christian beliefs such as the virgin birth

and the deity of Jesus Christ.

7. The Enlightenment made God an object in the universe, rather than a personal being. This

identification broke the link between God and the tradition of scripture, liturgy, practice and

thought that was a mark of the medieval church. God was perceived to be an immaterial entity

that/who (?) could nevertheless interact with the material world. Such a construction produced

obvious problems with the theology of the nature of God, creation, divine inspiration of the

Scriptures, the Incarnation of Jesus Christ (as the Son of God, not just a moral example, or a

Teacher), His resurrection, and the message of Redemption and eternity.

8. In Enlightenment thought, human subjectivity replaced God (cf Romans 1:22). Each and every

individual becomes his or her own reference point; there is no single truth, and no assurance, no

moral or spiritual compass, just each person's opinion.

- The weakness of this approach is that every individual will assume that his or her

"rational" opinion is sound. Christians must avoid the temptation of relying on personal

experience, feelings and opinions as truth apart from the test of revelation in Scripture.

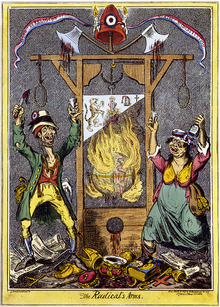

The End of the Enlightenment

It is difficult to date precisely when the Enlightenment era ended although some point to the

French Revolution.

"There is an air of naivety about the so-called 'Age of Reason'. In retrospect it seems

extraordinary that so many of Europe's leading intellects should have given such weight

to one human faculty - Reason - at the expense of all the others. Naivety of such

proportions, one might conclude, was heading for a fall; and a fall, in the shape of the

terrible revolutionary years, is what the Age of Reason eventually encountered."

(Davies, N, p. 577)

In today's "postmodern world" (and after two world wars, a cold war and ongoing conflicts)

many key assumptions underlying the Enlightenment have been rejected, including overconfidence

in reason and the innate goodness of man inevitably leading to an enlightened

society.

If the church is to become an authentic voice in our time it must confront the false alternatives

that have come down to us from the Enlightenment and proclaim a God who is real and a

theology that is faithful to the Bible and the early church and is relevant to our era.

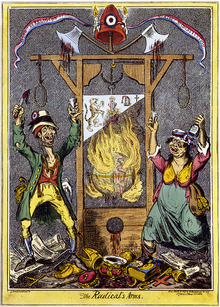

French Revolution

American Revolution

Issues Facing Christians During this period

- "Enlightenment" is a loaded word if it is used in the context that the previous period/s

were the "Dark Ages".

- Can a rationalist be a Christian?

- Rationalism in the context of the Enlightenment is the belief that all knowledge

comes from pure reason, or the mind. It excludes revelation. It is subjective, cf

"What is truth?" (John 18:38). Rationalism rejects the deity of Christ, the Bible

as the Word of God, and salvation by faith in Christ alone. Christians must

embrace factual learning and discoveries, but cannot allow non-Christian world

views dictate their faith. If truth were determined by reason, spiritual events and

all experiences would be subject to the limits and conditions of rational

examination.

- However, Christianity is not irrational. It involves believing in a personal God, and

following Jesus Christ His Son, worshipping Him, and obeying His commands.

Since the time of the Apostles and the Church fathers Christian apologists have

sought to explain the Gospel and defend the faith from attacks by unbelievers.

- Christians are not anti-intellectual, but must remember that, " '...my

thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways,' declares

the Lord. 'As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways

higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts' ". (Isaiah

55:8, 9)

- Christians are commanded to understand the reason for the hope that is in them

(1 Peter 3:15)

Additional Reading

Blainey, G, A Short History of Christianity, Viking, Melbourne, 2011

Davies, N, Europe: A History, Pimlico, London, 1997

Lion, A Lion Handbook, 1990, The History of Christianity

Miller, A, Miller's Church History: From the First to the Twentieth Century

Renwick, AM, The Story of the Church, Intervarsity Press, Edinburgh, 1973

Wright, J, The Jesuits: Missions, Myths and Histories, Harper Perennial, London, 2005

Rationalist House, Auckland